Ali & Nino

The Business of Literature

Who wrote Azerbaijan’s most famous Novel?

in

“Azerbaijan International” 2011

A Review

by Hans-Jürgen Maurer

Foreword

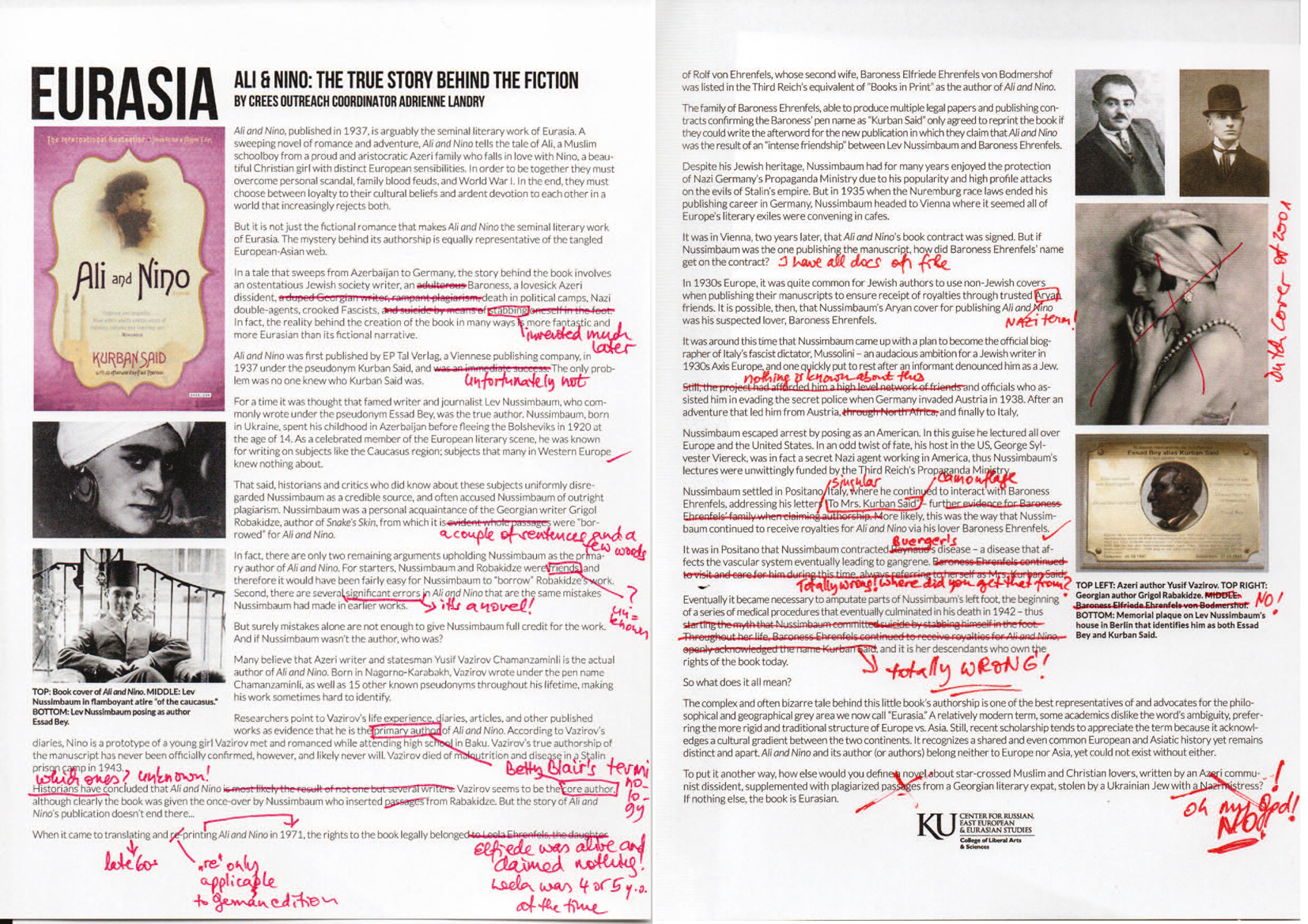

In September 2011 the notable British Newspaper, The Guardian, published an article with the headline “The vanishing fascination of truly anonymous authors”. In it the author Daniel Kalder gives a brief but excellent overview of the fight over the question “Who is behind the author Kurban Said who wrote the novel Ali & Nino?”. Reading this article I was particularly glad to learn that there are other people are out there who own a sense of discrimination when it comes to the problems described. Kalder writes:

Thus if you visit the book’s [Ali & Nino] Wikipedia page you will see that some very helpful people have 1) declined to mention Reiss’s book [The Orientalist] even though it was a bestseller in several countries, 2) indulged in some character assassination aimed at Nussimbaum (which is nothing compared to the muck flung at him on his biographical entry), and 3) advanced the thesis that the „core author“ is the „Azerbaijani writer and statesman“ Yusif Vazir Chamanzaminli, apparently on the basis of DEEP textual analysis, although they admit that Essad Bey’s „fingerprints“ are on the book – yucky! Of course, the refusal to name Reiss’s book on the Ali and Nino Wiki page is indicative of the extreme insecurity the invisible editors have regarding their claims.

Below this article five reader’s comments can be found, of which I assert bluntly that four were written by the “invisible editors” of the wikipedia manipulation, who is merely just one editor, namely Mrs. Betty Blair of Los Angeles, USA. No one else on the face of this earth promotes the idea of the Azeri authorship of “Ali & Nino” with more fierceness and near-religious fervor.

Betty Blair is the editor-in-chief of the magazine Azerbaijan International, a quarterly journal, whose numbers 1 to 3 for the year 2011 consisted of one big issue, entitled “Ali and Nino – The Business of Literature” – and my review here is about that publication. I feel the need and urge to reply to this publication because I believe that Betty Blair has gone too far, and that someone needs to speak-up to her. That’s why this review is written in a personal tone, not fearing polemics or even clear statements which may be sometimes regarded as blunt.

Daniel Kalder continues:

“In fact, these days when an author disappears it inspires in certain souls a mad detective hunt. Bitter wars erupt between scholars, and tremendous amounts of creative energy are wasted on quixotic pursuits of the author’s „true identity“.”

So I have to say, that my review here is meant to be a missile from (and into) the frontline of that “bitter war”. Hopefully I have not “wasted my creative energy” but used it to set a few things straight – or was at least able to present a broadened outlook on statements given in Betty Blair’s unfortunate – or should I say “infamous” publication.

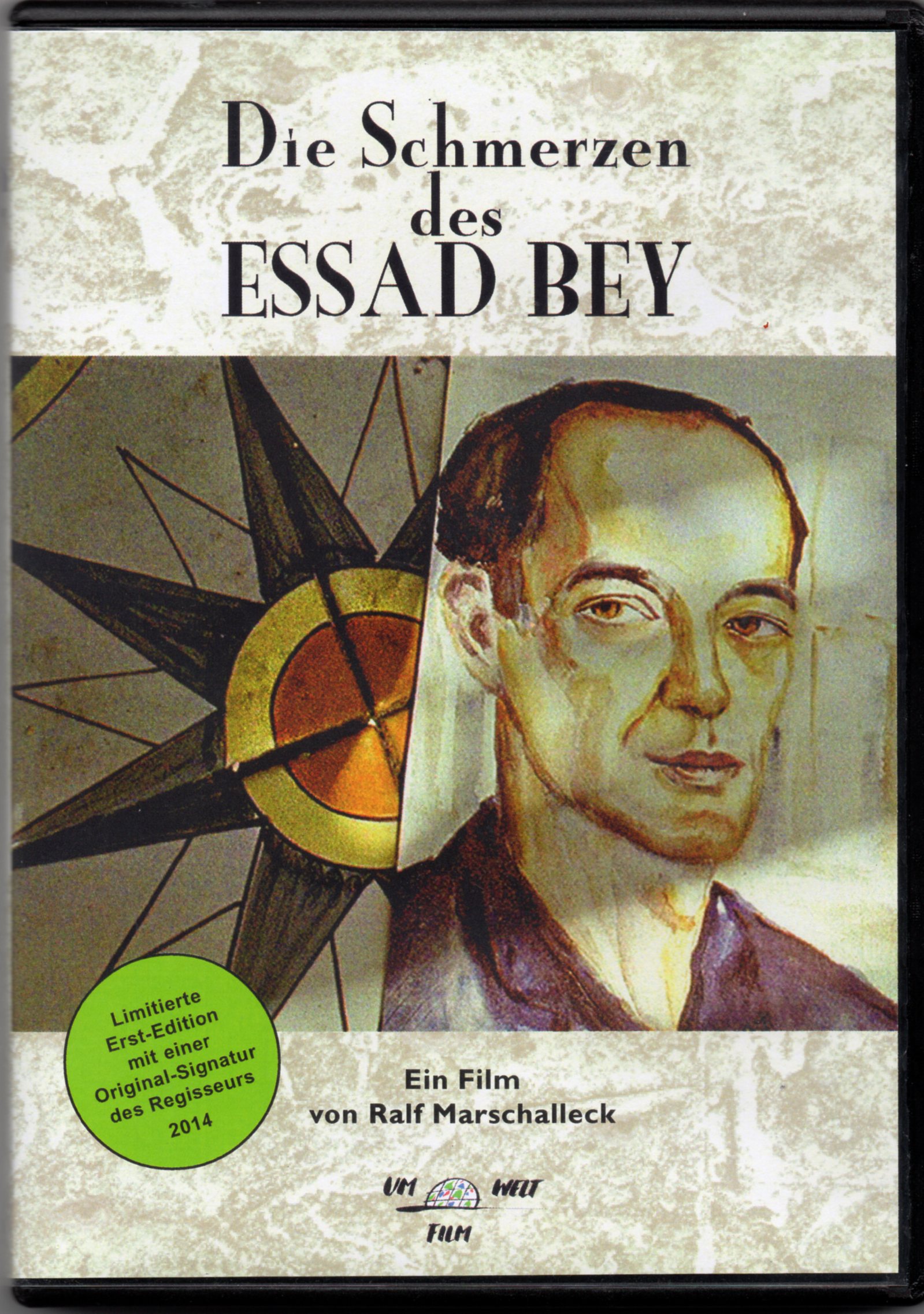

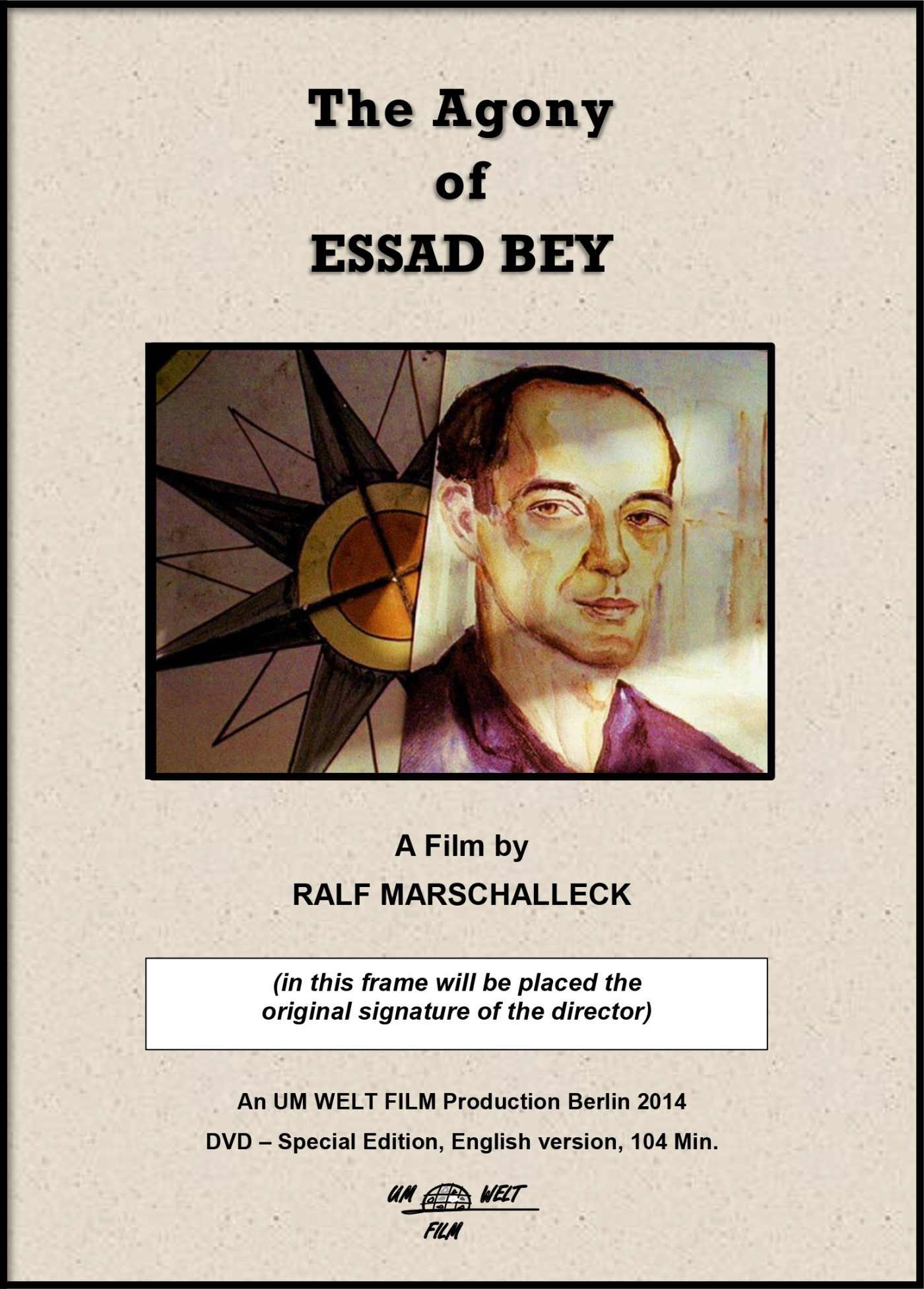

The subject matter is complex and covers a vast ground. Years have been spent in study and research as well as in constant reflective discussion with fellow researchers; and indeed it takes its own time to find one’s way through the jungle of facts related to the life of Lev Nussimbaum a.k.a. Essad Bey a.k.a Kurban Said – and everything around it.

I would like to add that this review here probably will not be enjoyed by the “uninitiated” reader. This is due to the reasons mentioned above and due to the fact that I as the reviewer address my text to those who have at least some insight into the problems around Ali & Nino. But I wish this text to be at least an eye-opener for anyone who wants to take the risk and read Betty Blair’s publication.

Kindly bear with the reviewer in regards of English grammar, orthography and punctuation. He ist neither a native English speaker nor has he never lived in an English speaking country. If you find typos, give him a friendly yell by e-mail.

And so I should like to close this foreword with the words Daniel Kalder concluded his article with: By all means, do enjoy reading Ali & Nino!

Introduction

2011, when this volume came out, „Azerbaijan International“ was already in its 16th year of publication. Award winning and America-based, it used to appear four times yearly in Los Angeles and Baku. Editor Betty Blair created this “independent publication, which seeks to provide a forum for discussion and thought related to Azerbaijanis throughout the world”. In the year 2011, however, something was different. The magazine “Ali and Nino – The Business of Literature” alone forms three of the four yearly issues, consisting of impressing 364 pages, and it should really be called “a book”. And this I am going to call it from here on.

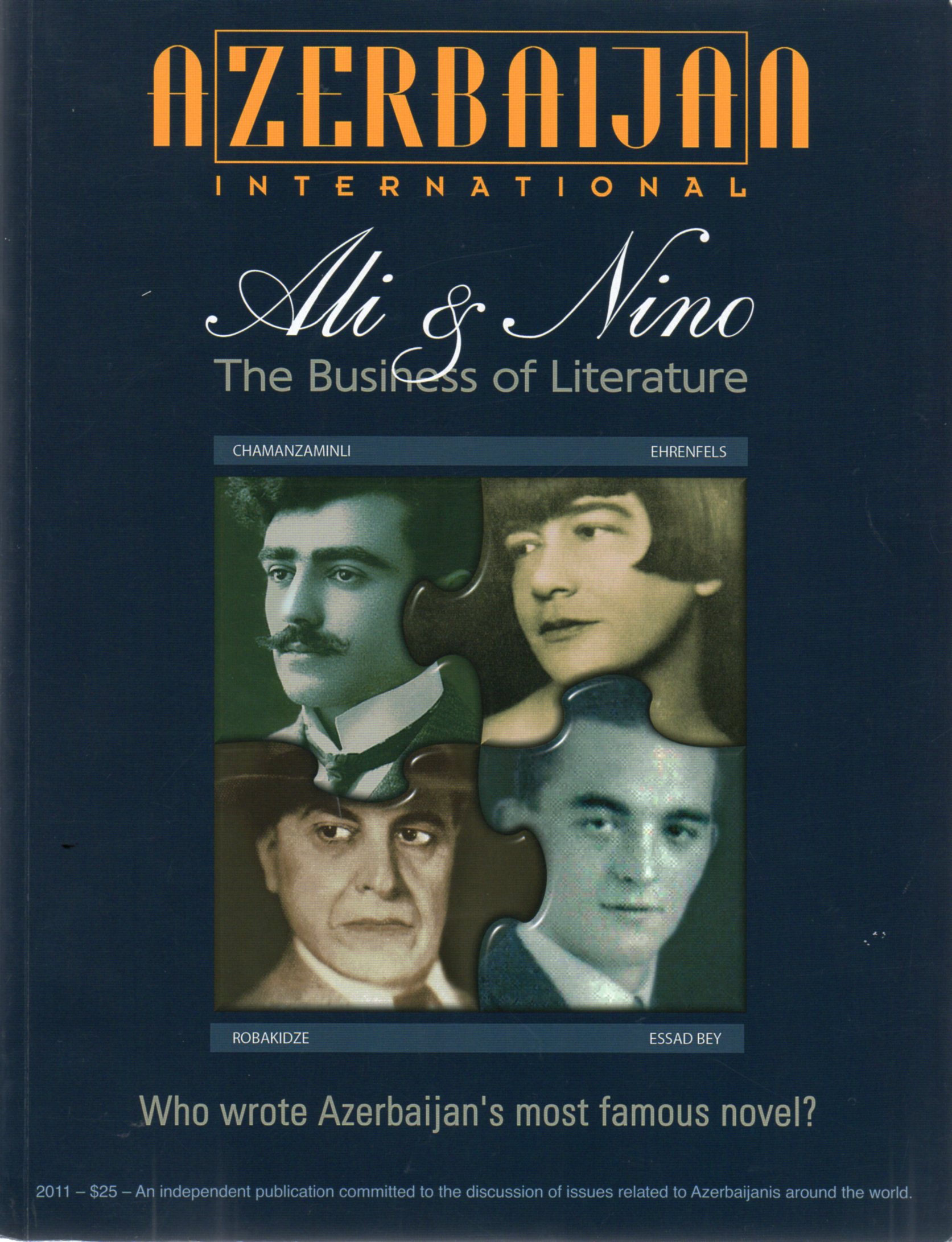

The big “magazine”, having the measures of the American Letter Size format and weighing 1,3 kilos, is on the table in front of me. The paperback cover shows the portraits of four authors: Azeri writer and statesman Yusuf Vezir Chemenzeminli, Austrian Baroness Elfriede von Ehrenfels, Georgian writer Grigol Robakidse and Essad Bey. These four portraits are designed as interconnected pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. This is a clever allusion to the content of this work, because the whole issue is quite puzzling.

Below the cover image I read the subtitle, at which at once I come to a halt: “Who wrote Azerbaijan’s most famous novel?”

This does not sound right, because “Ali & Nino” is certainly not “Azerbaijan’s most famous novel” but rather “the most famous novel in Azerbaijan” – or perhaps “the most famous novel playing in Azerbaijan”.

I must insist on this subtlety – why, will be shown further down.

Thumbing-through

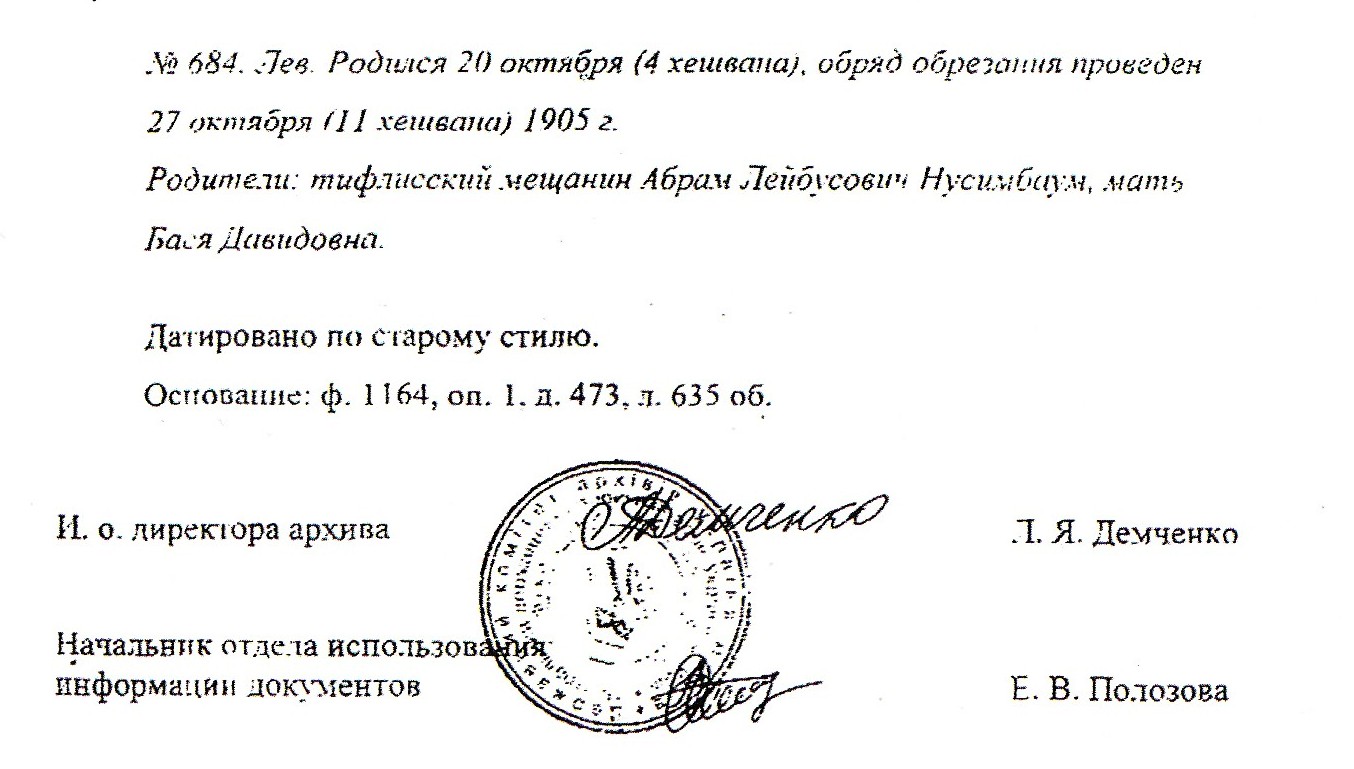

I open the book and I am overwhelmed and in awe by my first impression. Images over images on these 364 pages – many hundreds, many of which were never seen before (at least not by me). Century-old postcards from Baku, maps, buildings, people, countless book covers. Some of these images are sensational, like Lev Nussimbaum’s birth certificate – published for the first time ever. Or the Ashumov building in Baku, the last residence of the Nussimbaum family – which obviously has been identified in the meantime. Wonderful!

The impressive table of contents gives us almost forty chapters which deal with the question “Who is the author of Ali and Nino?”

It is very obvious: researching, collecting and filing of the presented info was a gigantic task. Here may be mentioned that the reviewer is a writer, publisher and a typesetter himself and knows what he is speaking about.

Let’s jump to page 18 and marvel at more than 80 book covers of Ali & Nino in 36 languages. On the back of that double page we find the portrait photos of 60 (!) people who contributed over the years to this voluminous work in one way or another. These photos are supplemented by introductory texts about each single of these helpful people, which cover more than 11 pages to follow.

Chapeau, Betty Blair!

Now let’s take a look at the chapter “Frequently Asked Questions”.

On pages 52 through 95 158 questions are posed and answered – the 158 answers are pointing towards further 543 end notes presented on 43 pages, which round-off and back-up the answers given before. (However, this was just one chapter.)

The publisher says that this book contains 1200 photos. Indeed I am overwhelmed and I can only but admire the quality of design and layout.

Beginning to read

But then I began to read. Already in the first minute I began to frown, thinking: “No, you can’t put it this way, this is not quite precise.” Or: “No, there’s no proof for this statement, how can you present this as a given fact?”

This went on and on – no matter on which page I was reading.

So I tried another strategy: I kept on reading, but took notes about each sentence, which contained errors, or was incorrect or simply wrong. However, after one hour I had to give up. I had not even covered one page of the book – and not even written down every comment or correction needed. I had no hope whatsoever to touch even the tip of the iceberg of all erroneous statements – most of which were not only erroneous, but also slanderous, superfluous, and – pardon me – stupid.

Do not be discouraged by my stern and frank words here, keep reading on, I will explain the best I can.

As I said, I had to stop my initial plan of commenting each single sentence which needed commenting. For a few weeks I felt to be at the end of my wits. Questions over questions formed in my mind. I could not understand how the editor, who seems to be an experienced journalist with an enquiring mind, can be contented with carelessly throwing half-truths, assertions, insinuations and distortions to the readership of this book – which, out of necessity – can only be of the uninitiated kind. Nobody who has not studied the whole subject for at least one year – if not longer – will have developed a sort-of „inner compass“ that guides one through this vast field of knowledge. Indeed, the available info about Essad Bey is immense.

Now the most pressing questions in my mind were: WHY THIS BOOK? and WHAT FOR?

Will I be able to answer them?

Disclaimer

I have to give a disclaimer here. I call this text of mine a review. But the points to be criticized in Ali and Nino – The Business of Literature are so numerous, that I can only touch upon a few of them. I picked them at random. Not commenting on other issues does not mean that I agree upon them. And the examples I picked for this review form in no way a hierarchy of “most important” – or the opposite.

The reason for this is simply that this book is – put quite frankly – a bottomless pit.

What follows here can be just A FEW examples. But even if they are few, they still represent as such the general make-up and quality of the reviewed work.

Why It Just Ain’t So, Betty Blair!

Example 1

An analysis of the usage of the terms “drug”, “drug dealer”, “hashish” and “pain”.

Betty Blair says more than 16 times in her book that “Giamil Vacca Mazzara was a drug dealer” (as on pages 39, 47, 92, 211) and that Essad Bey took Hashish (pages 47, 81, 92, 108, 133, 151) and morphine (page 131, quoting someone else).

Uuuuuh – bad people! A drug dealer and a drug taker! WOW!

Does this not shed a bad light on both Essas Bey and Giamil Vacca Mazzara?

Well, if you’re as lucky as the proverbial blind squirrel fining a nut once in a while, you may have found the – only two – instances which do justice to Essad Bey and Vacca Mazzara – by saying WHY the latter provided the previous with drugs: namely to kill the excruciating pain he was suffering from his disease (pages 131 and 151). And in one isolated other paragraph on page 131 Betty Blair explains why this was indeed necessary: because “during the war [morphine] would have been difficult to acquire.” This quote is not Blair’s own observation but a reproduction of Essad Bey’s statement – however, formulated in a conditional form.

Essad Bey did suffer from the “Buerger-Syndrome“, a disease of the blood vessles in the feet and legs, which let E.B.s foot rot on his living body, causing excruciating pain. World War II was in full go by that time and almost all available morphine was needed at the front to treat wounded soldiers. Also the local pharmacist in Positano was tired to provide the pennyless patient Essad Bey with this rare drug.

Now, who would deem it fair to label Giamil Vacca-Mazzara – who most likely was indeed a very doubtful figure – simply as a „drug dealer“? And call Essad Bey simply a „drug addict“? After all it was him, giving the sufferer a few painless hours here and there.

I find it most irritating that Blair knows these facts and yet does not hesitate to use a few details so selectively in order to slander our protagonist. The ratio between 16 mentionings and only 2 clarifications – sprinkled over 363 pages – is too poor to be fair – or should I say „heartless“?

Example 2

Referring to page 56, number 24, dealing with the assertion that Ali & Nino could not have been written in 1936/1937 but much earlier, in order to convey the pain and suffering in such fresh way.

Quote:

“The story [A&N], undoubtedly, could not have been written with the same poignancy and pain had it been penned in 1936 – 16 years after the tragic events had occurred. Time anesthetizes and blurs the memory. The throbbing pain ceases. It only seems logical that the novel was written much earlier.”

Actually, such a statement is too silly to comment on. A good writer can invoke ALL emotions in a reader. That E.B. was able to write “with the same poignancy and pain” was certified by award winning German Islamic Scholar Navid Kermani. In his review about E.B.s book “Allah is Great” (written together with Wolfgang von Weisl), published in the notable German weekly “Die Zeit”, Kermani mentions also E.B.s biography on the prophet Mohammed:

“… But above all Bey was a brilliant, intoxicating sylist. Bey is writing a German that nowadays hardly exists among non-fiction writers, even less among experts on Islam. It has rhythm and uses harmonious imagery, is rich in semantic and syntactic variants and he understands so much of the arc of suspense, that this carries the author away from historical facts towards possible but not proven fiction. His biography on Mohammed […] has no place in specialised libraries – but as reading matter for the vespertine hours of the day one could not think of a more entertainig depiction, which in addition captures the spirit of the early islamic history much better than any source-critical monography.” (Highlighting be me.)

In other words: Essad Bey was very well able to bring a time alive which was just two decades ago, as in Ali & Nino. He has proven this with his biography on Mohammed in which he depicts a time which is more than fourteen hundred decades ago. What else is “being a professional writer” about?

Example 3

Treament of Essad Bey’s Novellas

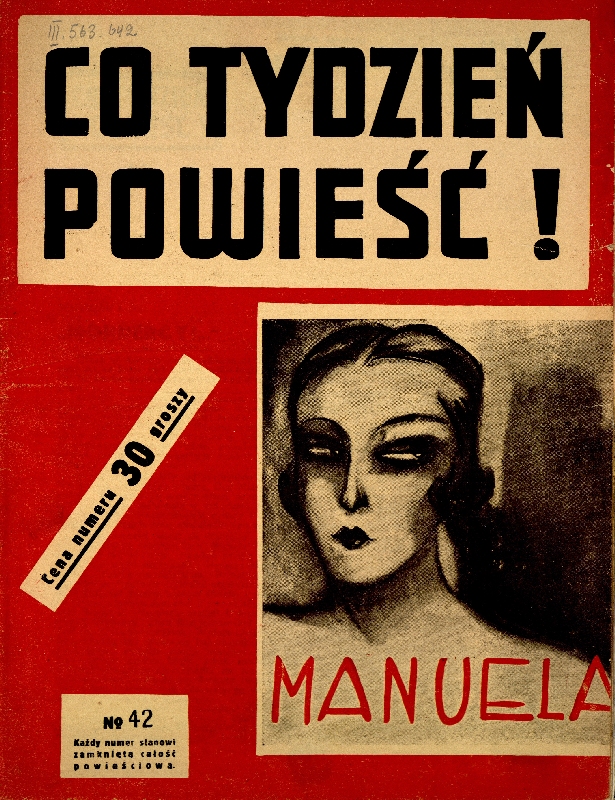

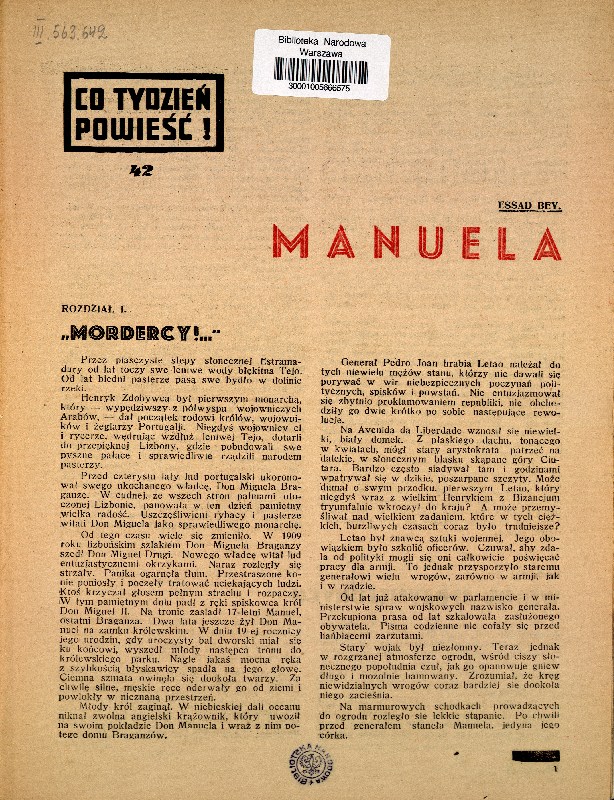

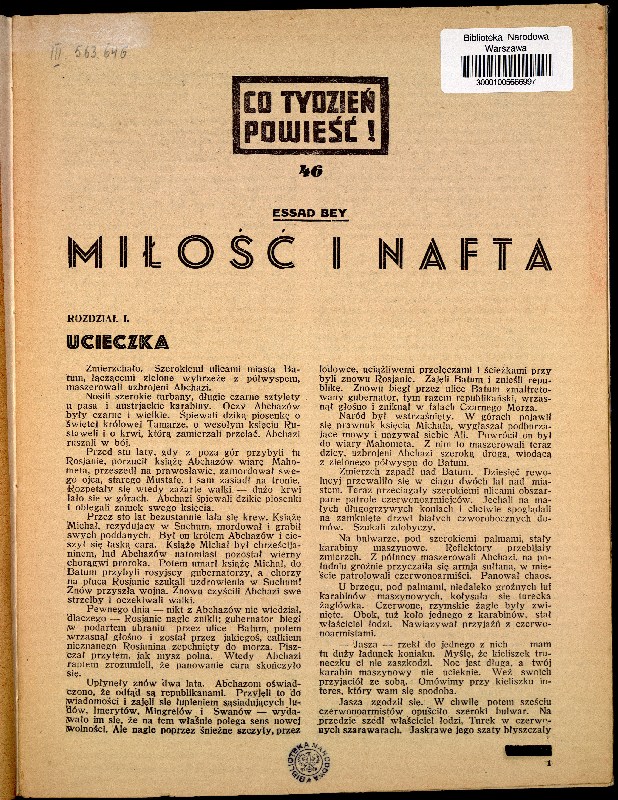

In 1934 appeared two novellas, or rather “pulp novels” in the Polish series: “Co Tydzień Powieść” (“A new novel each week”, published in Łodz, Poland: Republic Publishing House).

They bear the titles “Miłosc i nafta” (Love and Petroleum), and “Manuela”.

Blair frequently quotes Georgian scholar Dr. Zaza Aleksidze. He had had the chance to read the novels in their Russian translation (published by ISSC in Baku), so he was able to inform Blair about the novellas.

We cannot agree what he says about them: „Essad Bey’s fiction is simplistic and primitive when compared to Kurban Said’s masterpiece Ali and Nino”, (AI, page 162, Endnote 60)

This disagreement is based upon the ground that the whole concept of these two novellas is such as of mere pulp novels, also called in English “penny dreadfuls” or “dime novels” – clearly proven by the fact that the two stories were written to fit into a line of pulp novels.

Yes, the style is not sophisticated, but it was never meant to be. And yet, the content of the two novels is far from being primitive. Essad Bey would not be Essad Bey if he hadn’t written about the major themes of his life: oil, the world of high finance, bolshevism, revolution. And so he did here. Essad Bey weaved world history together into two simple stories which are not merely invented for cheap emotional effect and entertainment (which is usually the purpose of pulp novels).

To make a statement like “Essad Bey’s fiction is simplistic and primitive …” shows either the total lack of deeper knowlege and consideration, or the aim to suppress holistic information. But it clearly shows how the editor of this book uses each little sign to bend the truth to fit her purpose. And this purpose is “Essad Bey bashing” or, as the Daniel Kalder puts it in his article in The Guardian: “character assassination”.

Further Blair, who has NEVER read these stories – she obviously speaks only one language – further comments on Essad Beys two pulp novels on page 313, right column:

“His protagonists are involved with the dark world of intrigue, seduction, blackmail and revenge in their quest to acquire big money and power.”

What does one expect of dime novels? But as mentioned above, the basic plot of these stories happened more or less like this in real life – and there they DID play in the dark world of intrigue and blackmail!

These words here are used by Blair just for the sake to shed a dim light onto Essad Bey – using the same pulp fiction methods.

For further insight into Essad Bey’s two pulp novels see my essay which is published here on this blog in German and English.

Example 4

Treatment of Hertha Pauli

AI, page 75, number 81, and the respective endnotes

Pauli, Herta E. („Bertha“ is wrong). „Letter to the Editor about Authorship of Ali and Nino,“ in New York Times Book Review (August 8,1971), p. 27.

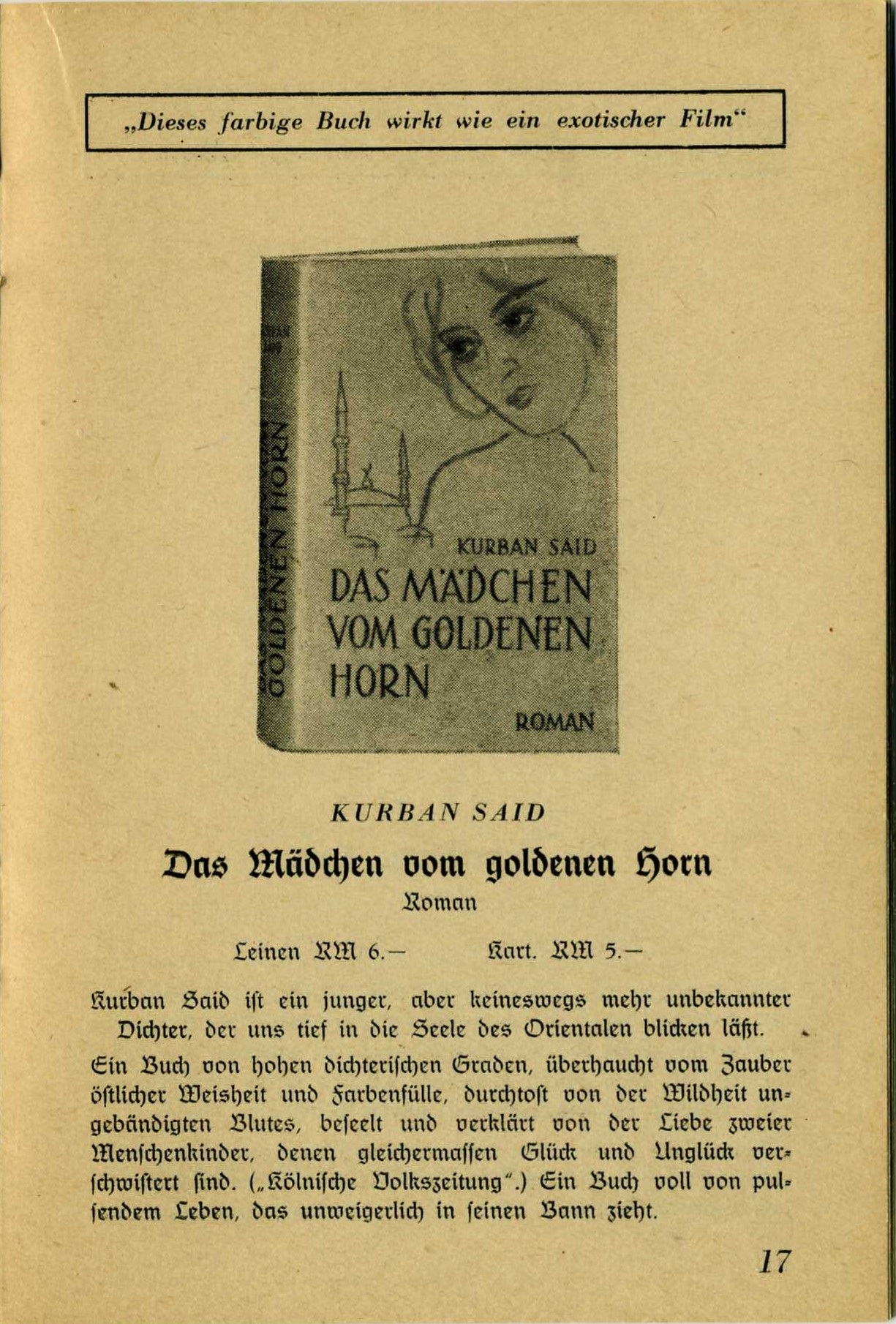

Mrs. Hertha Pauli (1911–1973) was Essad Bey’s literary agent during his time in Vienna. She and her business partner Karl Frucht was responsible for the deal with Zinnen-Verlag for “The Girl from the Golden Horn” and for many adventure stories they solf ro E.B.

On June 27, 1971, The New York Times published an article entitled: “The Last Word: Who Wrote ‘Ali and Nino’?” which follows the claims Yusif Kahraman and Mustafa Türkekul of Washington D.C. That’s another story to be told somewhere else. In short: The two exiled Azerbaijanis read the novel, recognised names, streets, palaces, historical events, but had no clue who the author „Kurban Said“ might possibly have been. They simply added 1 and 1 together and claimed the author only could have been Yusif Vezir Çemenzeminli. That’s how this unfortunate theory was born. After they’d written to Random House, the editors there informed the New York Times and Walter Clemons worte the above mentioned article, following Kahraman’s and Türkekul’s theory.

But shortly after Walter Clemons’s article appeared in The New York Times, they received a letter by Hertha Pauli, which was deemed important enought to be printed in The New York Times on August 8, 1971. This letter reads:

To the Editor:

May I add another word to Walter Clemons’s exciting „Last Word“ (June 27) about the authorship of „Ali and Nino“? I just have to tell you that I read the novel at the time of its successful, first publication, 1937, in my native Vienna and talked to the author himself about it.

To my knowledge „Kurban Said“ was Essad Bey, a colleague and friend of mine, whose nonfiction books were translated into many languages and can still be found at the New York Public Library.

I met Essad Bey in Vienna in 1933; he had come from Berlin, where the Nazis had taken over. He was then in his 30’s and looked somewhat like King Hussein without the mustache, and his wit and charm were most engaging. He joined a writers‘ cooperative, „Austrian Correspondence,“ I had organized to provide authors whose work was „undesirable“ in the Third Reich with opportunities for publication elsewhere. Essad Bey was soon contributing numerous articles about the history and customs of his Transcaucasian homeland.

Essad came from a Transcaucasian Jewish family named Nussinbaum and took the name Essad Bey when he turned Moslem. He never made a secret of his ancestry; he spoke of it openly in his usual amusing fashion. This may have been why he wasn’t publicly attacked during those years of rising anti-Semitism in Vienna.

The biographical data you quote from the introduction to „Ali and Nino“ corresponds exactly to what Essad told me. When his homeland Azerbaijan was taken over by the Soviets in the early twenties he went to Berlin and launched his career as a writer. (He told funny anecdotes about his learning to write in German and about his knowing Stalin when Stalin was still Djugashvili —“a highwayman.“)

At the Cafe Herrenhof in Vienna, where we met regularly, I also sometimes saw his old father, who seemed to me like an odd character of one of his son’s books.

Essad Bey stayed in Vienna till 1938, when he fled, like myself, because of the Anschluss. He went to Italy, where he would be safe, and died there soon after from elephantiasis.

„Ali and Nino,“ his only novel, was the one book for which he used a pseudonym, because, he said, it was so different from his serious non-fiction. (Another reason may have been that as „Kurban Said“ it could still be sold in the German market.)

The new, excellent English translation brings the German original vividly to my mind; I seem to hear Essad talking again in his particularly witty way, especially as the stage is set at the beginning of the book.

Bertha Pauli

Huntington, N. Y.

Walter Clemons replies:

Miss Pauli’s identification of „Kurban Said“ as Essad Bey is reinforced by a letter to Random House from Alexander Brailow, who knew Essad Bey first as a schoolboy in Baku and later in Europe. Four of Essad Bey’s books were published in America in the early thirties: „Twelve Secrets of the Caucasus“ (1931), and biographies of Stalin, Mohammed and Nicholas II.

Blair’s treatment of this subject on page 75, right column, and the two preceding lines reads like this:

“She prefaced her remarks in the Times with the caveat: “To my knowledge,” before adding her personal opinion that Essad Bey was Kurban Said. […] “to my knowledge” makes her statement conditional, as if she were hesitating to make an absolutely conclusive statement equating Essad Bey with Kurban Said.”

Since late Mrs. Pauli cannot defend herself and make her statement more precise, I will have to do it for her. Again, Blair would not miss the opportunity to drive her axe into this tiny cleft – or what she wants to be one. Unfortunately she forgets the fact of the language barrier. The subtleties of a foreign language (English, in this case) cannot be learned fully by an adult. Hertha Pauli was an adult when she arrived in the USA. If Blair spoke any foreign language she would know about this.

Hertha Pauli’s native language was German, and in our language is it perfectly alright to use this phrase without losing credibility – she says nothing but: “It is my knowledge that Kurban Said was Essad Bey.” It is a polite way of speaking – quite obviously something alien to the author of that book.

And what about the heavy content in the rest of the letter? No, Blair is just hovering upon three words in a half-sentence. Do not be mistaken by Hertha Pauli’s conscientious and polite way of speaking. After all this is to be preferred over the insinuative, unconstructive manner and the suspecting criticism in which Blair’s whole volume is written as a whole.

What really strikes me here: Where Hertha Pauli uses the polite phrase “to my knowledge”- after confirming in the sentence before, that she has talked to the author himself about this book, Blair, in the rest of her book, speaks always with full authority about things he has no proof for.

And some proof against her theories are being suppressed by herself:

When The New York Times printed Hertha Pauli’s letter, which was a reply to Walter Clemons’ article, the latter added to Hertha Pauli’s letter:

Miss Pauli’s identification of „Kurban Said“ as Essad Bey is reinforced by a letter to Random House from Alexander Brailow, who knew Essad Bey first as a schoolboy in Baku and later in Europe. Four of Essad Bey’s books were published in America in the early thirties: „Twelve Secrets of the Caucasus“ (1931), and biographies of Stalin, Mohammed and Nicholas II.

This reply is printed right under Pauli’s letter. It was suppressed by Blair in her publication!

Example 5

Flowchart on double page 152-53

The flow chart on the double page shows books by Essad Bey in the sequence of their published date.

It is headed by this insinuative question: “Did he really write all those books published under his name?

Most of the displayed book covers have BBs comments, and here follows some comments of mine on those comments.

a) A New York Times review of 1932 about “Stalin”: “A dangerous book …. the average reader… may be misled.”

At that point in time Essad Bey was the first one to fully understand fully Stalin’s regime and impact on the world. Most of his contemporaies – even intelligent papers like The New York Times, still believed in the good revoluationary spirit of Stalin – a disastrous misconception. Essad Bey was the first warner – unheard unfortunately.

b) “Liquid Gold”: “Many passages are unlike Essad Bey’s style.”

I don’t know which edition Blair has read. It does not exist in English and it is unlikely that Blair speaks more than her native tonuge. I have read the German original, and, being an editor, publisher and writer myself, I declare, that the whole book is typically Essad Bey.

c) “Love and Oil”: “How is it that E.B. knew the geography of Atchara in Blood and Oil” but not here in Love and Oil”?

Well, “Love and Petroleum” (which would be the correct translation) and along with it “Manuela” were intended from the beginning to be nothing more than pulp novels. And this is all that needs to be said.

d) “Caucasus” “… written by an Armenian point of view…”

So what? This only proves that Essad Bey transcended his nationality and upbringing and that he was not a nationalist – unlike the influence behind the magazine Azerbaijan International.

These few examples must do. If someone is interested in learning more, go and study.

…. to be continued …