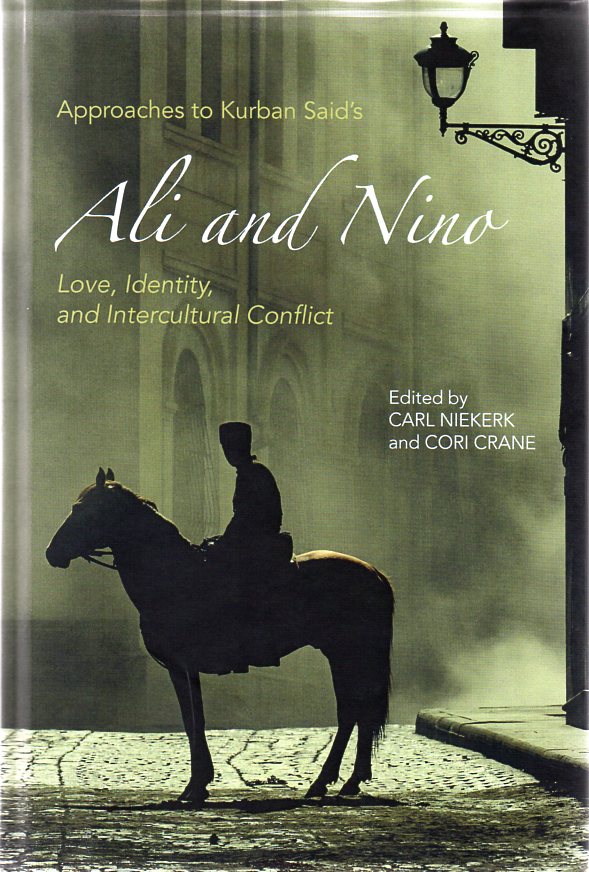

Approaches to Kurban Said’s ‚Ali and Nino‘

Edited by Carl Niekerk and Cori Crane

ISBN 978-1-57113-990-0

Camden House, Rochester, NY, USA

Finally I received the long-awaited book! First I had had the chance to read parts of a chapter online on Google Books, so I knew the book wouldn’t disappoint me.

In fact, as Essad Bey’s current German publisher, expert on Essad Bey’s life and particularly on the publication history of Ali & Nino, most considerations of literary science are of lesser importance to me personally. Nevertheless I do love the fact that the novel is taken so seriously – and it should be!

The chapter I was able to read online (at least parts of it) was No. 7: „Love and Politics: Retelling History in Ali and Nino and Artush and Zaur“ by Daniel Schreiner. This tickled me especially since I happen to know the author of Artush and Zaur, Alekper Aliyev, and I’m somewhat familiar with the somewhat unfortunate history of his novel. I also read the German and English manuscripts. But that’s a different story.

In this review I am only going to speak about Carl Niekerk’s and Cori Crane’s „Introduction: Ali and Nino as World Literature“, for an introduction must have the biographical and more general info about Kurban Said / Essad Bey.

To be precise: I am not going to speak about the text in general, I want to point out errors and give my opinion on some statements.

I have great respect for the editors, they are scientists of literature, and I welcome this book greatly. As far as I know this is the first attempt to look at Ali & Nino academically – after Gerhard Höpp’s most valuable texts from over 20 years ago.

Since the authors and editors of this volume here hardly have had reliable sources from which to draw waterproof biographical information about Lev Nussimbaum’s / Essad Bey’s / Kurban Said’s life, they are excused for this matter.

Here we go:

On: „INTRODUCTION: Ali and Nino as World Literature“

Comments by Hans-Jürgen Maurer, Frankfurt/Germany

Page 1:

a)

Here the questions are asked: „Why was the novel written in German?“, „Why in 1937?“

Essas Bey was a German writer. We know of some Russian love poems he’d written in his youth to his great love Zhenia Voronowa. And he may have contributed Russian texts to publications in his early years. Undoubtedly Russian was his first language (spoken in his family – I know picture postcards he’s written in the 1930s to his aunt in Paris). But after his mother’s suicide when he was five years old he learned German from his governess.

As a writer of magazine articles and books he clearly was a German author.

So the question „Why was the novel written in German?“ to me sounds like a rethoric question.

Why was the book published in 1937? By that time, Essad Bey was living from hand to mouth again (the authors are hinting at that on page 3). We do not know anything about the motivation for this love story. The inspiration for topics an author chooses at any given time will be a mystery forever. And who cares, really?

So for me the question „why 1937?“ is neither a valid one – in my opinion. You write what you’re inspired to write. Why was the Carl Niekerk’s book published in 2017, not in 2015? You see what I mean?

A&N must have been a fairly easy book for Kurban Said to write since he’s „recycled“ some earlier material of his in A&N.

It would be more interesting to ask about the resonance the novel had in society during that time of racism (and I could imagine that into the book this question will be discussed). Lucy Tal, the publisher, claimed in the 1970s that the novel had been a flop. I don’t believe that – it saw four editions at the time and they sold the rights for five foreign languages.

b)

In the last line of page 1 is stated that „Das Mädchen vom Goldenen Horn“ was published by the same publisher.

No, it was published by Zinnen Verlag.

Page 2:

a)

Quote: „Tom Reiss argues that the author of Ali and Nino is Lev (or Leo) Nussimbaum, born in Baku in 1905 …“

Yes, indeed, Tom says that. But back then we did not have the information we have today. Meanwhile the entry of Lev’s birth was found in Kiev. But that does not even say he was born exactly there, he was just registered in that Kiev Synagogue. Please see my other posting regarding Lev’s birth place.

b)

Quote: „In Berlin, Nussimbaum hid his Jewish identity and adopted the alias ‚Essad Bey’…“

Here it is not clear if this is still Tom Reiss quoted.

Lev did not hide his Jewish identity. There is a letter, written by Hertha Pauli, his later literary agent in Vienna to the New York Times, in which she said he never made a secret out of his ancestry. He even made jokes about it. She was talking of the Vienna years 1933 till 1938 – when it was more dangerous to be Jewish. But even in Essas Bey’s early Berlin years almost all of his friends were Jewish … Alexander Brailow, the Pasternaks, the Voronows, Yasha Zaguskin and many more. It was during his time at the Russian Gymnasium he converted to Islam. That’s why „Essad Bey“ is not an alias but his assumed name after his conversion.

This change of name he took very seriously. Alexander Brailow speaks about it in his unpublished memoirs (on file in my archive) – namely how Essad Bey had to „force“ his peers to address him by his new name and how they teased him about it. But likewise Brailow gives a dialogue between Essad Bey and the teacher, where the latter addressed him indeed as „Essad Bey“.

No known source says that he hid his ancestry. Hertha Pauli even said that he often was seen with his father, Abram Nussimbaum – to which she added, that „he looked like one of the quaint figures out of his son’s books“.

c)

Bottom of the page:

Quote: „Accordingly, all earnings associated not only with the German version of Ali and Nino but also with its many translations went to Elfriede von Ehrenfels herself and, after her death, to her heirs.“

This is wrong.

The royalties of 1937 until the early forties went to Elfriede von Ehrenfels – after all, she’s in the contract -, and were surely forwarded to Essad Bey. She then went to Greece where she stayed for many years.

In the meantime the book was forgotten.

When A&N became a bestseller in the 1970s Elfriede was aware of it but she neither claimed nor received a penny. It was clear to her and her ex-husband, Umar Rolf, that Essad Bey was the author. I have old correspondence on file proving this. This evidence will eventually be published in my own book.

Also, we know that Lucy Tal received most of the royalties from the book’s success from 1970 onwards, sharing it only in part with Jenia Graman who was very upset about it. That’s a seperate, complex, story which will be told in my book.

Elfriede was so dis-identified with A&N that she did not even put it into her will. Only about three years after her death the old publishing contract was found in her belongings and the now-Baroness, Mireille, had the court officially enter this contract retroactively into Elfriede’s will (copy on file). The benefactor of Elfriede’s will was Mireille’s daughter Leela. Elfriede’s heir, Leela Ehrenfels, received money after her lawyer enforced her right, but that was not before the final years of the 1980s (and she’s receiving money until today).

So yes, one part of the sentence IS right: after Elfriede’s death, the royalties went to her heirs. However, she died in 1984, but only after their laywer made his point in the late 80ies, the royalties were secured for the Ehrenfels family.

Page 3:

a)

Top line.

Quote: „The only evidence that the baroness’s heirs have offered to date in support of their relative’s authorship of Ali and Nino is that the alias „Kurban Said“ in 1937 was registered in Elfriede von Ehrenfels’s name.“

Well, „to date“ is unfortunately out-dated. They’re not saying anymore that auntie Friedel wrote the book, they simply point at the fact that the contract bears her name – and this is true.

They’re now putting it it this way: „We do not know who of the two, E.B. and aunt Elfriede, wrote what and how much, but the contract is in her name, so the money is ours.“

That story will have to be told elsewhere.

b)

Last third of first paragraph, the question of Çemenzeminli.

I will try to make this as short as possible, because this has become an awfully loaded topic.

After Random House had published the book in April 1971, newspapers printed book reviews of the novel. Two exiled Azerbaijanis in Washington D.C. were astounded at this book, the places, names, streets, history, all were real to them. They tried to make sense of the question who was behind „Kurban Said“. So they simply concluded it could only have been Çemenzeminli – who had been the professor for literature of one of the two now-Washingtoners: Mustafa Türkekul. They wrote to Random House. After the Random House editor Charlotte Mayerson talked to them, she informed the New York Times which wrote about this „discovery“.

But also two other people who were eager newspaper readers, Alexander Brailow (Essad Beys classmate in the Berlin years) and Hertha Pauli (Essad Bey’s literary agent in the Vienna years) wrote to the newspapers and/or the publisher giving their story, both stating that „Kurban Said“ was Essad Bey.

Their testimony weighed much heavier from the beginning, but the Çemenzeminli theory was born and slowly made its way eastwards – via Turkey to Azerbaijan.

Çemenzeminli has NOT written the book, no matter what Betty Blair says. As far as I am concerned she can stand on her head, wiggle her ears, and sound the mantra „Çemenzeminli“ for the next 100 years – she is mistaken. More about her and her unfortunate publication in my review on this blog.

The whole Çemenzeminli-idea was simply the fabrication of two exiled Azerbaijanis who tried to make sense out of this pseudonym – nothing wrong about it!

After all, they were interested and concerned. Unfortunately they were mistaken. The only real mistake they made is that they later INSISTED it must have been like that, no matter what.

More about this story in my forthcoming book.

Page 4:

12th line from above:

Quote: „… he died at the age of 37 on August 27, 1942“

Because he was born on 20 October 1905 he still was 36.

Page 5:

Bottom line:

Quote: „… Öl und Blut im Orient, his most successful book …“

Which one of his books his most successful one was remains to be researched. At least in the German speaking countries, Flüssiges Gold (Liquid Gold) was far more successful. That can easily be determined by the copyright page of the 2nd Swiss edition. But one would have to compare the international editions – of which there were quite a few of Öl and Blut, and Flüssiges Gold was never translated into English.

Stalin was perhaps even more successfull.

But nevertheless Öl und Blut im Orient was indeed successful.

Page 12:

Footnote 2 and 5, about the Wikipedia entry to Ali and Nino.

I can only refer to my forthcoming criticism of Betty Blair’s plentiful shenanigans.

… to be continued …

Schreibe einen Kommentar